My bad.

When a mistake or ill-advised post triggers a social media backlash, ignoring or deleting the problem can prolong the crisis.

Sometimes, the easiest way to diffuse a situation in social – and possibly even GAIN trust – is to admit when you get things wrong.

There are many ways brands can get it wrong in social media and cause a crisis.

- An innocent mistake – such as when a social media manager mixes up their accounts, sending an inappropriate personal comment from the brand.

- A technical issue or oversight – such as Uber failing to censor its Twitter bot from using offensive words, allowing it to be “slur-baited” by a troll.

- A tone-deaf campaign someone clearly didn’t think through before hitting publish – like Miele’s gender-stereotyping Facebook post for International Womens’ Day.

- An insensitive joke or badly judged meme

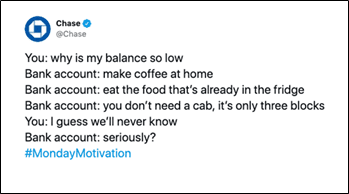

It is the last of these that caused Chase Manhattan Bank plenty of grief in 2019. The Chase social media team posted what it thought was a playful but otherwise pretty ordinary tweet that riffed on a recent meme.

Unfortunately, a lot of followers didn’t take well to being shamed by their bank for their grocery habits or deigning to buy the odd takeaway coffee.

Chase eventually deleted the tweet and posted a short non-apology that attempted to draw a line under the incident with a shrug.

It didn’t.

There are a few lessons to be drawn from Chase’s poor response.

You can’t delete your way out of a crisis

Sure, removing the offending post might prevent any more negative replies in that thread, but it might not prevent the backlash from snowballing further. It may even add more fuel to the bonfire.

You can bet there will be screenshots, allowing other threads to start and articles to be written.

Hours after Chase deleted its tweet and posted its non-apology, then-presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren tweeted her criticism of Chase – complete with screenshot – spawning another 27 thousand retweets and comments.

Plus, deleting the post can appear less like contrition and more like an attempt to whitewash the trouble away as if it never happened – particularly if it isn’t followed by any acknowledgement or apology. Speaking of which …

Apologise – quickly and unconditionally!

For some businesses – or, at least, some managers – sorry really does seem to be the hardest word.

But admitting to a mistake or apologising for getting something wrong shouldn’t be seen as weakness or failure. On the contrary; customers can be very forgiving of a business that admits when there is a problem and demonstrates a willingness to improve.

The longer a business holds out or ignores the backlash – likely hoping it will just fizzle away – the less genuine an apology will seem when it finally comes.

Back up the words with deeds

An apology isn’t worth much if nothing changes as a result. You also need to reassure followers that the same mistake won’t happen again.

While Uber was very quick to apologise after the racial slur incident, it also ensured the @Uber_Support account no longer uses the first word it detects in a person’s profile when replying to prevent the same error happening again.

The non-apology response from Chase doesn’t provide any clue to how it might change its approach in future. It doesn’t even acknowledge what it was about the initial tweet that caused the ruckus.

No business is infallible and no product is perfect. Strip away the branding, technology, strategy and spin and every business is really just a group of people doing the best they can.

And people are capable of getting things wrong every now and then. Your customers accept that.

Every relationship is built on trust, including between a business and its customers. Being honest and quick to respond when thing go wrong is one way businesses can demonstrate respect for their followers – and encourage followers to place more trust in them.

LET’S CONNECT